あしびきの山がくれなるほととぎす聞く人もなき音をのみぞ泣く

実方中将

あしびきの

やまがくれなる

ほととぎす

きくひともなき

おとをのみぞなく

auteur : 藤原 実方 fujiwara no sanekata, « capitaine du centre gauche » (中将)

rubrique : « 王昭君 » (wang zhaojun)

caché au fond des monts

le coucou

ne fait que pleurer

et personne ne l’entend

analyse brève

– « あしびきの » est un mot-makura (oreiller) qui appelle « montagne ». il n’a aucun sens en lui-même. plusieurs hypothèses tentent d’expliquer son étymologie (足引きの : gravir la montagne en « tirant les pieds » / le pied de la montagne qui s’étire / calembour médical / manyogana de roseaux et arbres / assignation de kanji arbitraire ultérieur de sens perdu…). ce mot renvoie immédiatement au poème 4 du hyakunin isshu. et il est stupéfiant, pour moi, que ce motif sonore, chanté, si immédiatement remarquable et « japonais » ne soit associé à aucune signification sauf celle d’introduire montagne (avec peut-être la nuance de lourdeur, lassitude ou isolement)…

– « 山がくれ » dit l’effacement, le retrait au fond des collines.

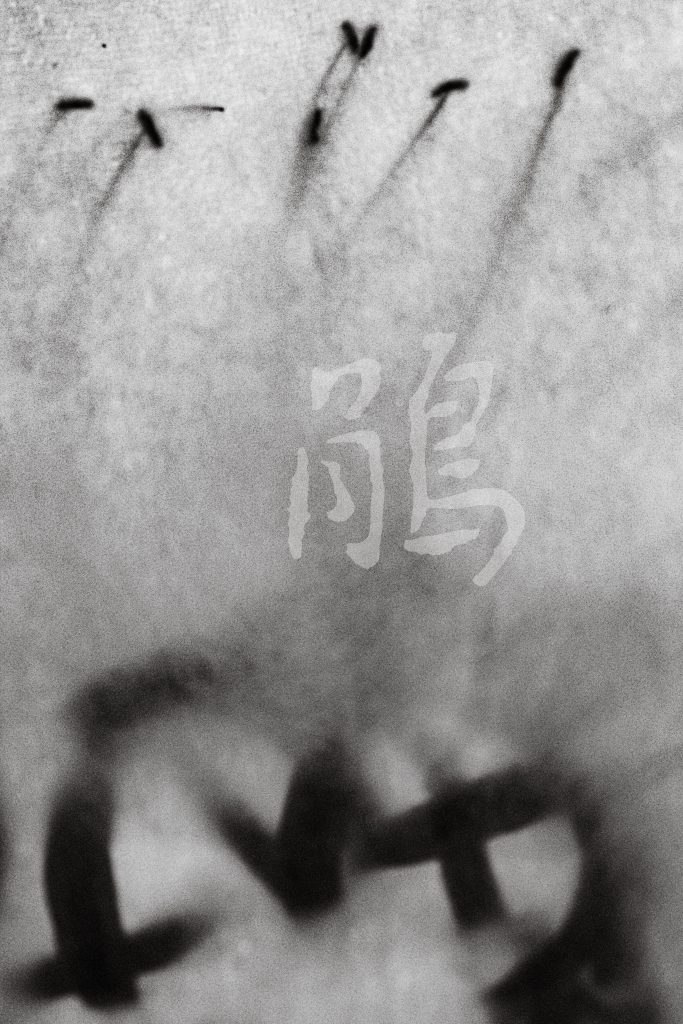

– « ほととぎす » le coucou japonais, l’oiseau symbole du chant plaintif : 鳴く = chanter / pleurer.

– « 聞く人もなき » : plainte sans témoin.

sanekata est envoyé loin de la cour comme gouverneur de mutsu (陸奥守 : 奥 renvoyant à la distance « au fond »), une province au nord est de honshu autour de l’actuelle sendai. sa mission est de rassembler de la poudre d’or pour le commerce avec les song.

poète de cour, militaire

réputé bon danseur

galant, aurait été l’un des modèles du genji

rumeur d’une liaison avec sei shonagon (qui nait en 966, la même année que fujiwara no kintô ! même cercles, mais aucune connexion repérée ! elle meurt en 1017, à peu près à la date de création du wakan roeishu). elle rapporte dans ses notes de chevet l’apparition de son fantôme près des ponts de la kamo.

existe la rumeur d’une querelle publique, à propos de poésie, avec le calligraphe fujiwara no yukinari (connu pour sa copie de poèmes de bai juyi !), dont il aurait jeté à terre, le chapeau, altercation à la suite de laquelle l’empereur ichijō l’aurait « envoyé voir des utamakura » au nord. mais les dates et d’autres anecdotes ne collent pas.

mutsu serait donc une punition (contexte peu clair) et kintô pense qu’elle est injuste (intrigue de cour ?) puisqu’il place ce poème dans la section wang zhaojun : non comme simple pièce saisonnière du coucou, mais comme écho japonais au motif « 昭君怨 » : la plainte exilée, ignorée.

le poème présent aurait été écrit non comme allégorie, mais d’abord comme expérience directe faite par le poète.

le poème est beau si au lieu d’en faire une explication longue et verbale, on le perçoit comme une expérience sensorielle enregistrée comme instantané sonore. qui symbolise – dans un deuxième temps – l’auteur. et qui prend une dimension supplémentaire par le classement par kintô dans cette section.

mais il faut avoir entendu au japon un hototogisu pour comprendre pourquoi cette expérience sonore seule est saisissante, préverbale.

insertion, parfaitement cohérente donc , sous la rubrique « 王昭君 – wang zhaojun » alors que sans tout ce contexte on aurait du mal à comprendre le classement de ce poème (d’homme japonais) sous cette rubrique traitant d’une femme chinoise.

il meurt en poste en 999. tombe à natori. la légende veut que sa mort soit un « châtiment divin » après être resté à cheval en passant devant un dōsojin-道祖神, la version shinto des actuels jizo bouddhistes (divinités protectrices des chemins), souvent représentés par des organes génitaux mâles et femelles, sur les routes. son cheval serait tombé raide sur lui.

il semblerait que saigyō, bashō ou shiki soient venus en pèlerinage sur sa tombe.

autre légende de sa vengeance postmortem : réincarnation en moineau pour manger toutes les offrandes sur les plateaux de la cour. révèle son identité dans le rêve du moine de kyôjaku-ji (suzume-dera 更雀寺 (雀寺) (京都市左京区)) qui enterre un moineau mort retrouvé dans son temple.

dicton : 勧学院の雀は蒙求(もうぎゅう)を囀(さえず)る

même un moineau, en vivant à proximité d’un lieu d’étude, finit par mémoriser les textes savants

poème 51 du hyakunin isshu

かくとだに

えやはいぶきの

さしも草

さしも知らじな

燃ゆる思ひを

« tu ne sais rien de mon amour pour toi qui brûle comme un tison »

à chaque fois, la façon dont tout est connecté subtilement, organiquement, mais dont les liens requièrent pour les comprendre des heures de recherche, me stupéfie.

à propos de mutsu et l’équivalence « barbares mongols du nord » et « barbares du nord au japon », il faut se rappeler que l’histoire est toujours écrite par les vainqueurs et qu’il est souvent difficile de bien repérer qui sont les « baddies » : souvent les méchants envahisseurs barbares du nord sont en fait des peuples qui défendent les bonnes terres qu’ils occupent contre l’invasion par le sud de peuple qui souhaitent les annexer, les taxer, les soumettre voir simplement voler leur terre en les repoussant au nord.

au japon, les méchants de l’histoire sont les emishi-蝦夷 (barbares insectes !), des populations aux traits proches des ainus, sibériens (barbus, « poilus », grands et roux : « démons rouges ») qui ne veulent pas être annexés à la cour yamato (nara puis heian).

les guerres actuelles sont de bons exemples d’actualisation du récit historique comme propagande.

english

author: 藤原 実方 fujiwara no sanekata, “captain of the center left” (中将)

section: “王昭君” (wang zhaojun)

hidden deep in the mountains

the cuckoo

cries and cries

yet no one hears it

brief analysis

– “あしびきの” is a pillow-word (makura kotoba) that calls “mountain.” it has no meaning in itself. several hypotheses attempt to explain its etymology (足引きの: climbing the mountain by “dragging the feet” / the foot of the mountain stretching out / medical pun / manyogana of reeds and trees / later arbitrary assignment of kanji with lost meaning…). this word immediately recalls poem 4 of the hyakunin isshu. and it is astonishing, to me, that this sonic motif, sung, so immediately striking and “japanese,” is associated with no meaning except that of introducing mountain (perhaps with a nuance of heaviness, weariness, or isolation)…

– “山がくれ” speaks of effacement, retreat into the depths of the hills.

– “ほととぎす” the japanese cuckoo, the bird symbol of the plaintive song: 鳴く = to sing / to weep.

– “聞く人もなき”: lament without witness.

sanekata is sent far from the court as governor of mutsu (陸奥守: 奥 indicating the distance “in the depths”), a province in the northeast of honshu around present-day sendai. his mission is to gather gold dust for trade with the song dynasty.

court poet, military man

reputed to be a good dancer

gallant, said to have been one of the models for genji

rumor of a liaison with sei shonagon (born in 966, the same year as fujiwara no kintô! same circles, but no proven connection! she dies in 1017, around the time of the creation of the wakan roeishû). she reports in her pillow book the apparition of his ghost near the kamo bridges.

there is a rumor of a public quarrel about poetry with the calligrapher fujiwara no yukinari (known for his copies of bai juyi’s poems!), in which he supposedly knocked off his hat, an altercation after which emperor ichijô “sent him to see some utamakura” in the north. but the dates and other anecdotes do not align.

mutsu would therefore be a punishment (unclear context), and kintô thinks it unjust (court intrigue?) since he places this poem in the wang zhaojun section: not as a simple seasonal piece on the cuckoo, but as a japanese echo of the motif “昭君怨”: the exiled, unheard lament.

this poem would thus have been written not as allegory, but first as direct experience by the poet. the poem is beautiful if, instead of making it into a long verbal explanation, one perceives it as a sensory experience recorded like a sonic snapshot. which then, in a second moment, symbolizes the author. and which gains an added dimension through kintô’s placement of it in this section.

but one must have heard in japan a hototogisu to understand why this purely sonic experience is striking, preverbal.

insertion, therefore perfectly coherent, under the heading “王昭君 – wang zhaojun,” whereas without all this context one would have difficulty understanding the classification of this poem (by a japanese man) under this heading about a chinese woman.

he dies in office in 999. tomb at natori. legend has it that his death was a “divine punishment” after remaining on horseback while passing before a dōsojin 道祖神, the shinto version of present-day buddhist jizō (protective deities of the roads), often represented by male and female genital organs along the paths. his horse is said to have dropped dead on him.

it seems that saigyō, bashō, or shiki came on pilgrimage to his tomb.

another legend of his posthumous revenge: reincarnation as a sparrow to eat all the offerings on the trays of the court. he reveals his identity in the dream of the monk of kyôjaku-ji (suzume-dera 更雀寺 (雀寺) (sakyō-ku, kyoto)) who buries a dead sparrow found in his temple.

saying: 勧学院の雀は蒙求(もうぎゅう)を囀(さえず)る

even a sparrow, living near a place of study, ends up memorizing scholarly texts.

poem 51 of the hyakunin isshu

かくとだに

えやはいぶきの

さしも草

さしも知らじな

燃ゆる思ひを

“you know nothing of my love for you that burns like a live ember.”

each time, the way everything is connected subtly, organically, but in such a way that the links require hours of research to understand, astonishes me.

about mutsu and the equivalence “mongol barbarians of the north” and “barbarians of the north in japan,” one must remember that history is always written by the victors and that it is often difficult to identify clearly who the “baddies” are: often the supposedly wicked invading barbarians of the north are in fact peoples defending the good lands they inhabit against the southern peoples’ invasion, who seek to annex them, tax them, subjugate them, or simply steal their land by pushing them north.

in japan, the villains of the story are the emishi 蝦夷 (“insect barbarians!”), populations with traits close to the ainu, siberians (bearded, “hairy,” tall and red-haired: “red demons”), who do not want to be annexed to the yamato court (nara then heian).

today’s wars are good examples of the updating of historical narrative as propaganda.

日本語

作者:藤原実方 fujiwara no sanekata、「左中将」(中将)

項目:「王昭君」(wang zhaojun)

山の奥に

時鳥(ほととぎす)

泣くばかりに

聞く人もなし

やまのおくに

ほととぎす

なくばかりに

きくひともなし

簡略な分析

– 「あしびきの」は枕詞で、「山」を呼び起こす。自体には意味がない。その語源については諸説ある(足引きの=山を「足を引きずりながら」登る/山裾が延びる/医学的な掛詞/葦や木の万葉仮名/後世の恣意的な漢字付与による意味喪失…)。この語は直ちに『百人一首』第四番の歌を想起させる。そして、この響きの型、歌われる音調、あまりに鮮烈で「日本的」なものが、山を導く以外に何の意味も与えられていないことは、私には驚くべきことである(そこには重さ、倦怠、孤立といったニュアンスがあるのかもしれないが)。

– 「山がくれ」は、山中深くに退くこと、隠れ去ることを示す。

– 「ほととぎす」日本の杜鵑、哀しみの歌の象徴となる鳥。鳴く=歌う/泣く。

– 「聞く人もなき」=証人なき嘆き。

実方は朝廷から遠く離れ、陸奥守として派遣された(「奥」は「奥深い」「遠い」を意味する)。陸奥は本州北東、現在の仙台周辺の国であり、宋との交易のために金粉を集める使命を負った。

宮廷歌人、武人

舞踊に巧みと評判

風流にして、『源氏物語』のモデルの一人とされる

清少納言との関係が噂された(966年生、藤原公任と同年!同じ文化圏に属するが、直接の関わりは不明!1017年に没、ちょうど『和漢朗詠集』成立の頃)。彼女は『枕草子』において、鴨川の橋辺にその亡霊を見たと記している。

また、書家藤原行成(白居易の詩の写本で知られる)との間に、詩に関する公の口論があったという噂もある。実方は行成の冠を打ち落としたともされ、その争いの後、一条天皇が「北へ歌枕を見に行け」と命じたとも伝わる。しかし年代や他の逸話とは符合しない。

したがって、陸奥下向は罰であったと思われる(背景は不明)。しかし公任はこれを不当(宮廷の陰謀か)と考え、この歌を「王昭君」の部に収めた。単なる季節の杜鵑の歌ではなく、「昭君怨」の主題──流され、無視された嘆き──への日本的呼応として。

この歌は寓意ではなく、まず詩人自身の直接の体験として書かれたものであろう。長々しい説明ではなく、音としての瞬間的経験を感覚的に捉えるならば美しい。その後に作者自身を象徴する。そしてさらに、公任の配列によって一層の意味を帯びる。

だが、日本で実際にほととぎすを聞いたことがなければ、この音の経験がなぜ言語以前に心を打つのか理解しにくい。

よって、この歌が「王昭君」に置かれたのは、まったく整合している。背景を知らなければ、日本の男の歌が中国の女を扱う項目に収められている理由は分かりにくい。

999年、任地で死去。名取に葬られる。伝説によれば、その死は「神罰」であった。道祖神(神道における地蔵的存在、道の守護神で、男女の性器を象ることが多い)の前を馬から降りずに通ったため、馬が急死し彼を圧死させたという。

西行、芭蕉、子規がその墓を参詣したともいう。

また別の伝説では、死後に雀に転生し、宮廷の供物を食べ尽くした。やがて京雀寺(更雀寺・京都市左京区)の僧の夢に現れて自らの正体を明かす。その僧は寺で見つけた死んだ雀を葬っていた。

諺:「勧学院の雀は蒙求を囀る」

学び舎の傍らに住む雀でさえ、やがて経典を覚える。

『百人一首』第五十一番

かくとだに

えやはいぶきの

さしも草

さしも知らじな

燃ゆる思ひを

「君は知らぬ、我が恋は炭火のごとく燃えているのに」

すべてが微妙に、有機的に結びついており、その連関を理解するには長い探求を要する。そのたびに私は驚かされる。

陸奥と「北方蒙古の蛮族」「日本北方の蛮族」の同一視について言えば、歴史は常に勝者が記すものであり、「悪者」が誰かを見極めるのは難しい。しばしば「侵略してくる北方の悪蛮族」とされた人々は、実際には南から侵入し併合・課税・支配、あるいは単に土地を奪って追いやろうとする勢力に抗い、自らの良地を守る人々であった。

日本における「悪者」とは蝦夷(「虫の蛮族」!)である。彼らはアイヌやシベリア人に近い特徴をもち(髭が濃く、毛深く、大柄で赤毛=「赤鬼」)、大和朝廷(奈良・平安)に併合されることを望まなかった。

現代の戦争もまた、歴史叙述が宣伝として更新される好例である。

中国語

作者:藤原实方 fujiwara no sanekata,「左中将」(中将)

栏目:「王昭君」(wang zhaojun)

藏身山里

杜鹃

只会哭泣

而无人听见

cáng shēn shān lǐ

dùjuān

zhǐ huì kūqì

ér wú rén tīngjiàn

简要分析

– 「あしびきの」是一个枕词(makura kotoba),用来引出「山」。它本身没有意义。关于其词源有多种假说(足引きの:攀登山岭时“拖着脚”/山脚延伸开来/医学双关/以万叶假名记作芦苇与树木/后世随意赋予汉字而导致本义失传……)。这个词立刻让人想到《百人一首》第4首。令人惊讶的是,这个如此鲜明、歌唱般、极具“日本性”的声音母题,却除了作为引出“山”的词外,并没有任何确切意义(也许带有沉重、疲惫或孤立的细微色彩)……

– 「山がくれ」表示隐没,退入山谷深处。

– 「ほととぎす」指日本杜鹃,象征哀怨之歌的鸟:鳴く=歌唱/哭泣。

– 「聞く人もなき」:无人作证的哀叹。

实方被流放远离朝廷,任陆奥守(陸奥守:“奥”指“深处”的遥远之地),该地位于本州东北,即今日仙台一带。他的任务是采集金粉以便与宋朝贸易。

宫廷诗人,武人

以善舞闻名

风雅,据说是《源氏物语》人物原型之一

传闻他与清少纳言有私情(清少纳言生于966年,与藤原公任同年!同属一个文化圈,但没有确凿联系!她卒于1017年,约为《和汉朗咏集》成书之时)。她在《枕草子》中记载曾在鸭川桥畔见其鬼魂显现。

另有传闻说他曾在一次公开的诗歌争论中与书法家藤原行成(以临摹白居易诗闻名)发生争执,并打落其冠帽,由此惹怒一条天皇,后者“派他去北方见识歌枕”。但相关年代和其他轶事并不吻合。

因此,陆奥之任应是惩罚(具体原因不明),而公任认为不公(或为宫廷斗争),因而将此诗收入“王昭君”一栏:不是作为单纯季节性杜鹃诗,而是日本对「昭君怨」这一母题的呼应:流放的哀叹,无人理会。

此诗或并非寓言,而是诗人亲身体验而作。若不加冗长解释,而把它视为感官经验、录下的声音瞬间,则其美感自现。随后,它才象征诗人本身;再加上公任的编排,更具一重意义。

然而,只有亲耳在日本听过杜鹃(ほととぎす),才能理解这种纯粹的声音体验为何如此震撼、超越言语。

因此,将其收入「王昭君」栏目完全合理;若无此背景,人们难以理解为何一首日本男子的诗会被置于记述中国女子的栏目之下。

他于999年任上去世,葬于名取。传说其死为“神罚”:因骑马经过道祖神(神道版本的地藏,护路神,常以男女生殖器象征),未下马致敬,马遂暴毙压死于身。

据说西行、芭蕉或子规都曾赴其墓朝圣。

另有他死后复仇的传说:转生为麻雀,专食宫廷供桌上的祭品。后在京雀寺(更雀寺,京都市左京区)僧侣梦中自报身份。该僧曾埋葬过寺中发现的一只死麻雀。

俗语:勧学院の雀は蒙求を囀る

意为:即便是一只麻雀,若长期栖居学馆之旁,也会背诵经籍。

《百人一首》第51首

かくとだに

えやはいぶきの

さしも草

さしも知らじな

燃ゆる思ひを

“你对我燃烧如炭火的爱情一无所知。”

每一次,那些微妙而有机的联系,都需要长时间的考证才能看清,却总让我惊叹。

至于陆奥与“北方蒙古蛮族”及“日本北方蛮族”的类比,须牢记历史总由胜利者书写,而“坏人”的身份常难厘清:许多所谓北方入侵的恶蛮,其实是守护良田的部族,抵御南方企图兼并、征税、征服,甚至单纯掠夺其土地的势力。

在日本,史书中的“恶人”是蝦夷(意为“虫蛮”),这些族群特征接近阿伊努与西伯利亚人(多须发,毛发浓密,高大而赤发:被称为“赤鬼”),他们不愿被大和朝廷(奈良与平安)所吞并。

当下的战争,正是历史叙事被作为宣传而不断更新的鲜明例证。

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.